Specialisation is for insects – a product designer impacts the entire user experience

As you gain more experience in the design industry, conventional wisdom is to specialise in a particular area. People have written numerous articles about why specialisation is good for your career.

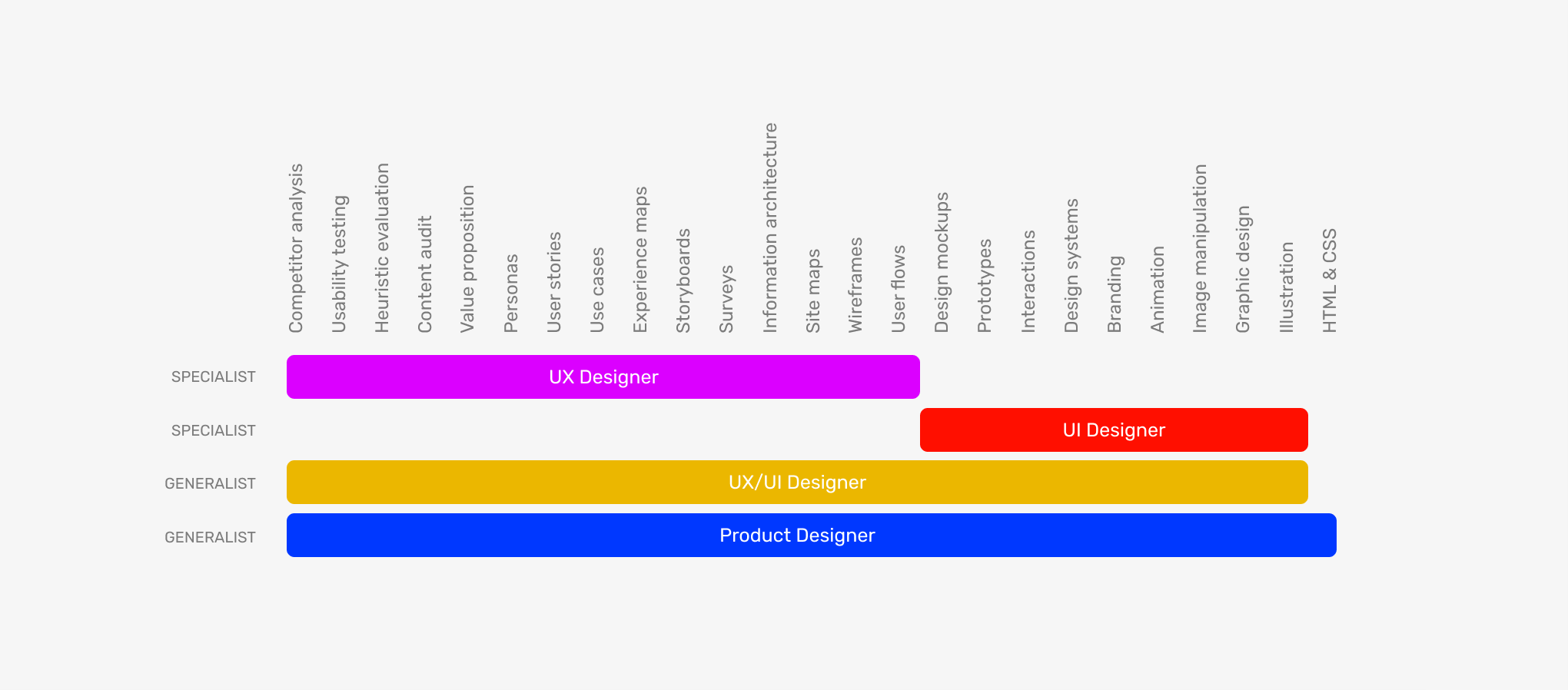

As the UX industry matures, more specific roles are popping up. Roles like voice designer, UX researcher, information architect, and interaction designer. These roles are far more specialised than the traditional UX/UI designer.

Specialisation makes sense. You can be an expert in an area by really delving into it. Owning it. Being the go-to person for that process in your company. But specialisation is not the only way to bake a cake.

I wrote this article to solidify my ideas. I want to understand my current aversion to specialisation. Why do I push back against it?

The argument for specialisation

Each man is capable of doing one thing well. If he attempts several, he will fail to achieve distinction in any – Plato

Expertise: Becoming super-skilled in your area. Being the go-to person for it.

Positioning: It's easier to position yourself if you're specialised. You're giving yourself a niche, which can make it easier to describe what you do.

Education: You don't need to learn such a dizzying array of skills if you're specialised. You can focus your learning efforts on a smaller target.

How can a designer specialise?

By role: UX researcher, UX designer, UI designer, voice designer, information architect, interaction designer.

By industry: Maybe you want to work in healthcare, or designing car dashboards. Choosing an industry with unique needs can be a great way to specialise.

By platform: Maybe you only design iOS apps. Maybe you only design email templates (please think very carefully before doing this!).

By ethics: Maybe you only want to design for not-for-profits.

What are the roles for generalists?

Product designer: I like this description from Jessica Lascar: "It’s about the entire process of creating usable products and experiences, starting by defining real people’s problems and thinking about possible solutions."

UX/UI designer: This title has never sat well with me. UI is a sub-set of UX, so I find it odd that you'd lump them together. You can't have UI without considering the UX. But I get the intention. It's the companies way of saying "We want a UX designer, that can also design polished interfaces, not just stop at a wireframe or user flow". I think this title is being used less as product designer becomes more common.

The argument for generalists

I've always felt that specialisation is best left to the insects – Gregory Benford

Variety: One day I'll be talking to users. Another I'll be designing interfaces. Another I'll be writing CSS. The variety of tasks activates different problem-solving methods. It stops me from burnout, from the monotony of doing the same thing each day.

Impact: Start with a problem and see it through to a solution. Be a bigger part of defining the problem and solving it. Moving the needle. Impacting the business, impacting the users.

Empathy: Build a sense of empathy for more areas of the process than if you're specialised. Writing some HTML and CSS helps give you empathy for engineers. Creating user flows helps you understand how hard it is to write detailed project requirements.

Cohesiveness: Carrying a problem to a solution.

Enjoyment: I love research, design and writing CSS. I want to do all of them.

Value: Impacting more areas increases your surface area for adding value to a project.

Employability: Generalist designers are extremely valuable in certain situations. Startups and small businesses without established design teams hire generalists to be flexible. To run the gamut of the design needs.

You need to draw the line somewhere if you're going to be a generalist

A while back, my team evaluated front end JavaScript frameworks for a new project. We chose to use React. Cool, a shiny new thing to learn!

The industry was already in love with React. I started an online course to learn the basics. Then decided to stop and take stock. I didn't want to spread myself so thin I became indistinguishable.

I realised that I needed to put a cap on how much I invested in learning JavaScript. As a generalist designer, I couldn't afford to become a front end dev as well. That's a step too far for me. I love coding designs in HTML and CSS and creating interactions with JavaScript, but becoming knowledgable on the React ecosystem was a huge addition.

So I spoke with the team. We agreed that I should have enough understanding to work within the React codebase, but not become a JavaScript developer. So I bailed on the React course once I had a solid understanding of the fundamentals.

This has proven to work well. I can now work in a React codebase. I do this as a designer who is improving interactions and working on visual components rather than a front-end dev who is thinking about handling state, performance, security, etc.

The industry is too large to be across it all, so you need to draw the line somewhere. Where you draw the line will most likely be different to me, but making a conscious choice is the important thing.

Is there a middle ground?

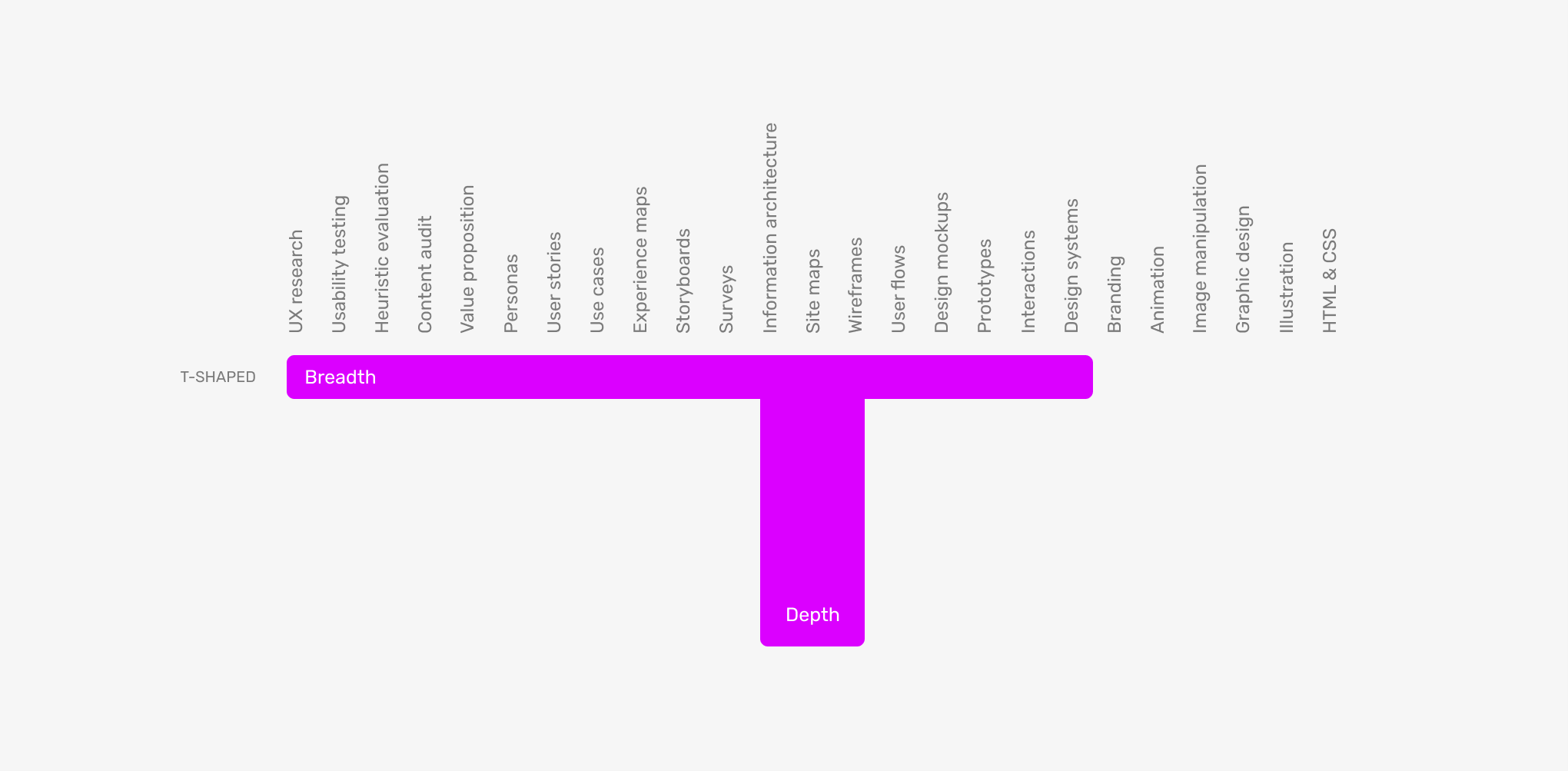

People who have a specialty, but also competencies in other areas are sometimes referred to as T-shaped.

Some years ago, Tim Brown of IDEO introduced the term “T-shaped” to describe people who have a depth of skill and experience in one discipline, represented by the vertical stroke, while also having breadth via skills and experience across other disciplines, represented by the horizontal stroke. He argued that the latter provided empathy for other disciplines and, in turn, fostered greater collaboration. Becoming a T-Shaped Designer

What feels right?

I'm a generalist by choice. Like everyone, I'm more experienced in some areas than others. That's unavoidable. Your experiences are a huge factor in determining what you're best at.

UX without UI feels unrewarding. I don't get to see the interface come to life. UI without UX feels like window dressing. The most interesting problems have already been solved by the time the UI designer gets involved.

As a designer working on digital products, being a generalist keeps me excited about my job.

So far I've served as a product designer across the whole process. But I don't need to be across it all equally. Being T-shaped might be the best of both worlds. A T-shaper can span the whole process while focusing on one area. But how do you choose that area to focus on? Or does it choose you?

Does it even matter?

If you find a role you enjoy in your team, the title might not matter. If you're doing good work, improving the product, helping users – well, that's what you've been hired for. Designers are problem solvers. So long as we're presented with problems, the job can be rewarding.

Summary

Specialising can be a good move for the career of an established designer, perhaps making them more employable in larger design teams that have specific needs.

Nevertheless, as of today, I hesitate to give up any of the parts of the design process I enjoy and can add value to. I want to use my breadth of skills to solve interesting problems. This is why I haven't specialised. This is why I choose to be a product designer.